Understanding what is happening in the bird’s gastrointestinal tract can lead to better flock health, more sustainable production and better return on investment.

The poultry gut microbiome is an extremely complex system that performs many more functions than simply digesting food and absorbing nutrients. Understanding a bird’s gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is vital to high productivity and optimal feed utilization.

“The gut microbiome is a complicated mystery to many producers,” said Briana Kozlowicz, manager of Cargill’s microbiome program. “In a single bird, there are thousands of organisms in the microbiome. A healthy gut microbiome is essential for a bird’s development and immunity and plays an integral role in maintaining the health of the flock.”

Modern science has begun to unravel that mystery — not only shedding light on how so many microorganisms work together to maintain a bird’s health and immunity, but also turning the microbiome into a window to a flock’s overall health.

While on-farm testing is not yet available, a growing number of private research institutes, universities and analytical labs offer sequencing and bioinformatic services to process microbiome samples, said Peter Karnezos, Ph.D., senior director for feed additive research at Land O’Lakes Inc. And analysis of this data can be used to identify the cause of otherwise unexplained instances of disease and poor flock performance, according to Henk Enting, senior technology lead for Cargill’s animal nutrition business, and Jean De Oliveira, animal science research at Cargill.

“The effects of feed, feed additives, medication, antibiotics, farm management practices, and other factors impacting the health of the bird can be assessed through analysis of the microbiome,” Kozlowicz said. “It’s important that producers understand how the choices they make impact broiler performance, health and preharvest food safety.”

Understanding the microbiome

The GIT has an extremely large surface area that is constantly interacting with the environment, according to Aoife Corrigan, Ph.D., research project manager at Alltech’s European Bioscience Centre. This means the GIT “must provide an effective barrier function which reduces exposure to environmental toxins and potential pathogenic microbes yet allow for nutrient absorption and waste secretion,” she said. “A further crucial functional component of the GIT is the development and maintenance of an effective immune system. The integrity, functionality and health of the chicken GIT depends on many factors including the environment, feed, and the GIT microbiome.”

In healthy and productive birds, the GIT microbiome population is in balance with itself and with the other members of the GIT ecosystem, Karnezos said. But stressors can disrupt that harmonization.

“When a stress event occurs and the ecosystem is disrupted, an imbalance in the composition of the ecosystem can result, allowing for pathogenic organisms to predominate,” he said. “A cascade of events that affect the health and performance of the birds ensues, including diverting energy to fuel the immune system, repair damage to the GIT, detoxifying harmful metabolites and toxins produced by the pathogens, and the beneficial microbiota struggling to re-establish the balance of the ecosystem.”

The stressors that can trigger this cascade can come in a variety of forms, from vaccination and handling to changes in diet and environmental conditions, Karnezos said. But regardless of what triggers the event, it can often lead to the same result: increased vulnerability to pathogens and disease, according to Mohamad Mortada, monogastric research scientist at ADM Animal Nutrition.

“Historically, we focused on the bird-pathogen interaction,” Mortada said. “However, we are learning that establishing an early life healthy microbiome is key to enhancing birds’ health and increasing resistance to enteric infections and various stressors. The gut is a primary contact site with various pathogens and harbors most of the bird’s immune cells. Therefore, maintaining the gut microbiome balance is central to gut health and overall health.”

Beyond opening birds up to more frequent bouts of disease, stressors may lead to an imbalance within the gut microbiome that can lead to inflammation, leading to decreased growth rates, poor feed utilization and mortality, Corrigan said.

“Increased microbiome diversity has been linked to greater resilience to challenges or stressors,” she said, “whilst low diversity has been associated with gut health problems.”

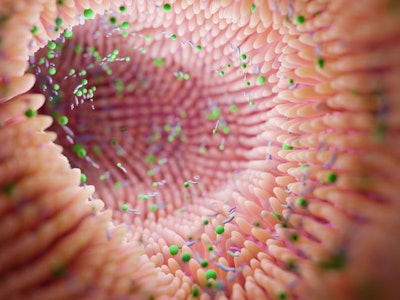

A healthy gut microbiome is essential for a bird’s development and immunity. (Alexander Baidin | Dreamstime.com)

A healthy gut microbiome is essential for a bird’s development and immunity. (Alexander Baidin | Dreamstime.com)Reading the microbiome

While the GIT is complex, technological advancements have helped scientists understand it better, Karnezos said.

“The poultry gastrointestinal tract is a complex sensory organ that houses a complex ecosystem of bacteria (both beneficial and pathogenic), viruses, bacteriophages, fungi and protozoa that exist in balance with one another and well as with the host,” he said. “The complexity of these interactions is far from fully understood, but with the advances in the ‘omics’ analytical technologies, we are learning more about the makeup and function of this ecosystem together with how it impacts the development of the GIT, (and) influences the host’s immune, endocrine and enteric nervous system.”

Zachary S. Lowman, of Balchem Animal Health and Nutrition’s monogastric technical service, pointed to recent advancements in 16S rRNA sequencing, which led to the discovery and classification of microbiota that was not previously cultured using conventional techniques.

“With the help of these new methods, researchers are discovering numerous links between the gut microbiome and chronic health issues within the poultry industry. Research has shown that some of these links include nutrition, gut development, immune function, as well as some bacteria in the microbiome that produce vitamins,” he said. “Now that we can study the gut microbiome in greater detail, we are able to develop customized probiotics and more specialized nutritional products to better address specific specie-related health challenges.”

Fortunately for producers, reaping the benefits of the scientific work is less complicated. Samples to be sent for laboratory analysis can be collected by producers using a simple non-invasive cloacal swab culture — similar to collecting a throat culture, according to Cargill’s Enting and De Oliveira. The samples are packed into a box for shipping, and the lab reports back about key biomarkers and insights.

Collecting data on related metrics is also recommended to help with the analysis. For broilers, this data might include information regarding mortality, feed conversion and body weight or, for layers and breeders, data on egg production, fertility and flock uniformity may be of interest.

“The gut microbiome has a dramatic impact on the overall health and performance of the bird, so all data collected throughout any/all production cycles is crucial,” Lowman said.

If a feeding program is achieving its desired effects, then the flock should show signs of improved performance via these metrics. But this isn’t always the case. Chicks will come from the same hatchery and receive the same nutrition and management, but may not have the same outcomes, Karnezos said.

“The question is, why is this the case? There can be a number of reasons, all of which have an influence on the microbiome and its complexity and diversity,” he said. “Taking samples from the GIT and the environment can help inform us of differences in the microbiome and how these differences are correlated to bird performance. This information can be used to develop management strategies to move (the) microbiome profile of the poorer performing flocks to look more like the better performing flocks, thereby raising the overall performance of the complex. Another approach is to use the analysis of the microbiome as a diagnostic tool to identify and characterize the pathogens responsible for a diseased state. These insights then can inform us on the approaches needed to mitigate the challenge.”

Microbiome analysis can yield insights as to the cause of discrepancies in flock performance, Enting and De Oliveira said. For example, excess protein or undigested protein in the hind gut indicates the presence of proteobacteria like C. perfringens and Listeria.

Specific bacteria respond to certain feed ingredients such as antibiotics and mid-chain fatty acids, Enting and De Oliveira said. Knowing which microbes may be present in the GIT can allow feed formulators to fine-tune the diet with respect to these ingredients, potentially improving gut health before signs of disease appear.

Providing pre- and probiotics to the birds can also help to nudge the microbiome in one direction or the other, Lowman said. And, he added, some strains of bacteria in the poultry GIT may help the bird utilize undigested feed to generate nutrients and energy such as vitamins, amino acids and short-chain fatty acids to help the bird achieve optimal performance.

Close monitoring of the bird’s gut microbiome means diets can be adjusted for optimum health, performance and feed utilization – and less waste.

“Understanding the microbiome makeup of a herd or flock in a timely manner helps Cargill and producers to determine if a diet is performing as expected, as well as the ability to recognize issues before they adversely impact health, welfare or the productivity of animals,” Kozlowicz said. “This allows us to respond sooner and more quickly in a proactive manner, whether it is suggesting changes to the diet or recommending a health intervention. Gaining this understanding earlier can lead to more precise diet formulation and better performance, which in turn translates into less waste and more sustainable production.”

Reaping the benefits

Many producers will try to improve their flocks’ health and well-being “based on intuition or anecdotal evidence,” Kozlowicz said, but they now have a much better insight into their birds’ health with information gained by studying the microbiome.

“With insights into the gut microbiome, producers have an opportunity to enhance their perception even more by understanding the microbiome’s connection to poultry performance. This can be achieved through recommendations from experts in the industry who have experience and access to data that can be used to provide actionable insights producers can use improve their farm management practices, and support flock health and performance,” she said. “Understanding the condition of the flock microbiome is the first step to improving the health of an operation.”

A healthy GI tract means optimal absorption of nutrients, but it also means so much more, as the microbiome plays an important role in immune function, Lowman said.

“There are studies demonstrating that the gut microbiome acts as a barrier to pathogenic bacteria by attaching to epithelial cell walls, helping to protect against the pathogens and contributing to improved performance,” he said. “However, the most common thought on gut microbiome function is competitive exclusion, which ensures there are enough ‘good’ bacteria to keep the pathogenic bacteria from growing.”

A bird with a highly functional gut microbiome will perform better and result in a better return on investment for the producer, Mortada said.

“A healthy bird has a higher feed intake and nutrient absorption than one challenged by disease. The improvement in animal performance results in an improvement in feed conversion and the cost-effectiveness of poultry production,” he said. “The bird’s gut microbiome is the root of its resiliency, or its ability to respond to and reduce the impact of external stressors. While a less resilient bird will be less likely to reach performance targets, a bird with a healthy gut microbiome is less susceptible to disease and may have greater consistency in production outcomes.”

Mortada added that enabling the bird to better absorb nutrients also creates less waste.

“We understand that animals with a healthy gut microbiome are better able to absorb essential nutrients, meaning fewer excretions into the environment,” he said. “We can also reduce waste by developing precise nutrition formulations tailored to an animal’s specific nutritional requirements. Essentially, sustainability and performance are two sides of the same coin.”

Karnezos agreed: “Using the information about the microbiome, we can implement feed additive technologies that help develop a healthy and productive microbiome that improves animal well-being, feed efficiency and weight gain, resulting in a more efficient use of resources. Less feed for more productivity, thereby lowering the carbon footprint for poultry meat and egg production,” he said.

Understanding the relationship between the gut microbiome and productivity will become increasingly important in the future, Corrigan said.

“The future of animal production is dependent on improved understanding of the interactions between the gut microbiome and the host physiological processes,” she said. “The ability to intentionally manipulate the microbiome to provide nutrients, modulate host immunity, inhibit pathogen colonization, or improve intestinal barrier function through the use of safe non-antibiotic alternatives will provide us new opportunities for the improvement of poultry health and production. Maintaining the balance of good gut health is a key aspect of getting the best growth and (feed conversion ratio) out of any food-producing animal.”

Announcing the Feed Mill of the Future digital supplement

WATT’s feed brands Feed Strategy and Feed & Grain magazines join forces to launch the monthly Feed Mill of the Future digital supplement. Each edition aims to provide animal feed industry stakeholders with forward-looking content, market insights and a spotlight on the leading-edge technologies shaping the global feed industry of tomorrow.

Subscribe today! https://bit.ly/3dWzow7